Backward Design

What is backward design?

The first step to producing quality online, blended or face-t0-face courses is quality course design. The most common approach to course design is to begin with a consideration of the most suitable methodologies for teaching content. In other words, the focus is typically on how the content will be taught, rather than on what is to be taught. However, Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe argue that this framework is flawed, because its emphasis on teaching methods is misplaced.

“Teaching is a means to an end. Having a clear goal helps us educators to focus our planning and guide purposeful action toward the intended results.”

In their excellent book, Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe propose the “Backward Design” framework for course design. This framework is “backward” only to the extent that it reverses the typical approach, so that the primary focus of course design becomes the desired learning outcomes. Only when one knows exactly what one wants students to learn should the focus turn toward consideration of the best methods for teaching the content, and meeting those learning goals.

See also: Instructional Design Models and Theories

The Backward Design approach consists of three phases: identify the desired outcomes; determine the acceptable criteria for evaluating students’ progress; and plan the instructional methodologies. For each of these phases, there are a number of benchmarks to help guide the course design process.

Stages of backward design

I. Identify the desired outcomes

In order to define the goals or learning outcomes for the course, you will need to formulate a clear idea of what students should know, understand, and/or be capable of doing. In addition, it is helpful to ask yourself what the impact of the course will be on students, and how you hope they will be different by the end of it.

In defining specific course goals, many teachers make use of A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing (Anderson, Krathwohl, 2001) as a guide. This taxonomy describes cognitive learning processes with respect to increasing levels of abstraction and complexity, from basic to advanced, around which goals can be organized.

- Remember: the ability to recover and access knowledge from long-term memory

- Understand: the ability to understand, interpret, classify, summarize and compare, and to construct meaning

- Apply: the ability to perform an unfamiliar task by applying previous knowledge to a new situation or problem

- Analyze: ability to organize, differentiate and attribute

- Evaluate: ability to judge, reason, and critique

- Create: ability to innovate and produce new knowledge

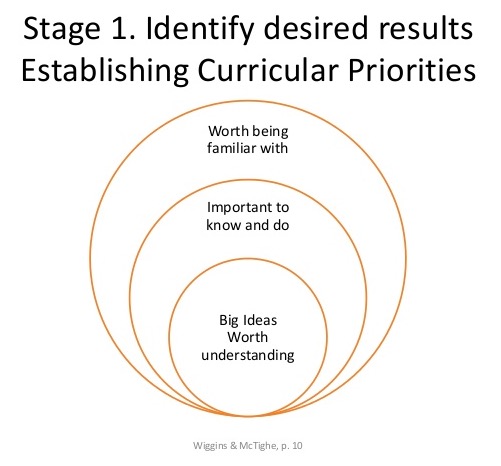

In addition to these guidelines, it is also helpful to categorize the goals you have for the course in order of importance. The reason for this is because within the limits of the course, such as time, it is likely that you will need to prioritize certain goals over others to ensure that the most important learning outcomes are achieved. To help you define the curricular priorities for the course, Wiggins and McTighe suggest the following three questions to help you progressively narrow in on and define the most important content areas.

- What content is it “worth being familiar with” for students? In other words, what is it worthwhile for students to read, discuss, hear about, or otherwise be exposed to?

- What content is “important to know” or “important to do” for students? What facts, principles, or concepts is it important (rather than simply worthwhile) for students to be familiar with? Are there processes, strategies, or methods that it is important for them to learn or be able to use?

- What “enduring understandings” do you want the students to take away with them, and retain and remember long after the course has ended? These are the essential “big ideas” or core concepts that students must understand in order to benefit from the course.

Identifying where various aspects of your course content fit within these three categories will help you clarify the specific, concrete learning outcomes that you have for your students, and will also help you decide how to structure the course to assist your students in achieving these goals.

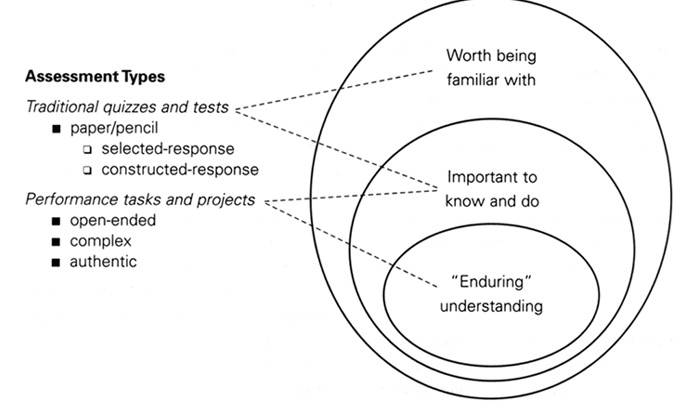

II. Determine appropriate criteria for evaluating students’ progress

This phase is essentially a way of helping you structure evaluative strategies into the course design so that you are able to gauge students’ progress towards the desired learning outcomes. In other words, this phase is intended to help you determine what criteria you will use to evaluate how well students are “getting it,” and what evidence you will accept with respect to evaluating their individual progress in mastering the course content.

There are, of course, numerous evaluative methods (i.e. essays, term papers, quizzes, lab projects etc.) that can give you feedback on students’ progress, knowledge, and skill level. However, not all of them are appropriate for every type of course, and knowledge. However, not all of them will be appropriate for every course, so it is important to choose those that align most closely with your learning goals, so that you can be sure you are testing for exactly what you want them to learn.

For instance, if a high priority goal of the course is to help students develop their problem-solving skills, an assessment designed to demonstrate these skills by having them write down the steps they took in resolving a problem, or an explanation of how they would approach an abstract problem (and why) will provide you with good insight into how skillful they are becoming at using problem-solving tools and strategies. On the other hand, if one of your important goals is to help students develop their ability to master mechanical tools, a problem-solving test may not provide you with the type of evidence of progress that you require.

It is worthwhile to keep in mind that certain teaching methods, such as lectures, facilitate learning at the more basic end of the taxonomy spectrum, while problem-solving, writing, and interactive strategies such as discussions and debates, encourage higher-order learning processes, such as analysis and evaluation. In choosing the strategies for your course, then, it is important to consider the levels of thinking, understanding, and reasoning that will best serve your desired learning goals for the course.

III. Plan the instructional methodology and learning experience

Once you have clearly defined and prioritized your goals for the course, and have decided on how you will evaluate students’ progress toward achieving them, the final step is to plan the instructional strategies and methodologies you will use in teaching the course. The most important question at this stage is “How can I create a learning experience for students that encourages them to engage with the content so that they are truly learning, and not simply passing assessments through rote memorization?”

Again, there are numerous strategies for enhancing students’ learning experience, and again, the ones you choose should align well with the goals you’ve defined for the course. For instance, exercises that are active and collaborative allow students to explore new concepts and idea in a relaxed way that encourages them to “own” them. Exercises designed to allow students to practice using new knowledge, or gain new skills, will give them a sense of mastery over the content that mere memorization cannot. Posing hypothetical questions or problems designed to allow students to apply new knowledge, or to practice newly acquired skills, will give them a sense of mastery that mere memorization cannot.

Forward Design Process vs Backward Design Process

Backward Course Design

We suggest that the Backward Design framework (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005) represents a more effective approach to both course design and redesign, and is appropriate regardless of whether the course takes the form of a lecture, discussion, or lab. The Backward Design framework puts student learning outcomes at the center, and offers teachers the flexibility to structure both the learning experience and the evaluative tools used to gauge students’ progress, so that they align appropriately with the course content, and so that they foster desirable learning outcomes.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P. W., Mayer, R. W., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning teaching and assessing. (Complete ed.). New York: Longman.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Chapter One of the book provides an overview, entitled “What Is Backward Design?”

Wiggins G, McTighe J (2006) Understanding by Design: A Framework for Effecting Curricular Development and Assessment. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development